Donley County is reporting no new cases of COVID-19 as of Tuesday, April 28, and Judge John Howard, MD, says it is safe for the county to adopt Phase One of reopening the state economy.

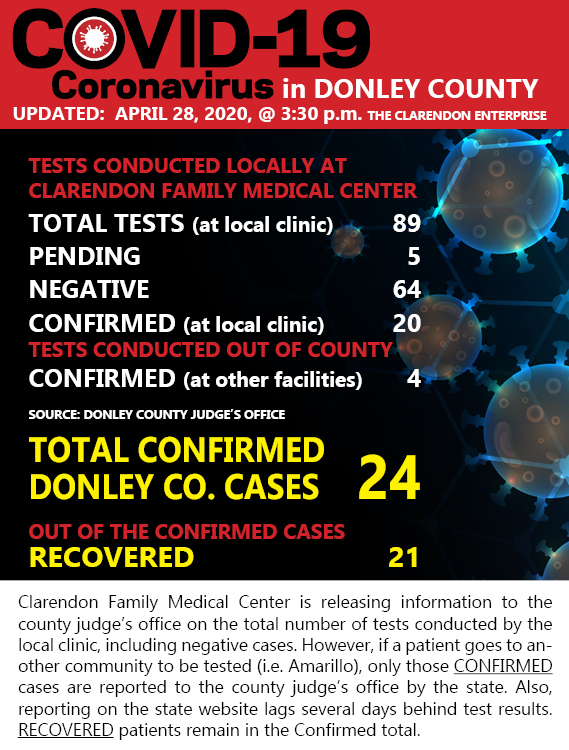

As the Enterprise went to press Tuesday, the Clarendon Family Medical Center had conducted 89 tests on local residents. Sixty-four of those tests have been negative, and 20 have been positive for COVID-19.

As the Enterprise went to press Tuesday, the Clarendon Family Medical Center had conducted 89 tests on local residents. Sixty-four of those tests have been negative, and 20 have been positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, four residents have tested positive at facilities outside of Donley County, bringing the total of confirmed local cases to 24. Twenty-one of those are now listed as “recovered.”

The results of five tests were pending on Tuesday. The last new postive case was reported by the Enterprise on April 21

“I think we’re safe to open in Phase One,” Judge Howard said Monday after the governor’s remarks. “Our community spread has been mitigated by implementing the requirements of GA 14 [the governor’s stay at home order].”

Howard reiterated that Donley County has done, as of last week, three times the testing compared to the state as a whole, which gives local officials more information to make decisions.

“This means we have a greater degree of confidence that the initial wave of community spread [of COVID-19] has subsided,” Howard said.

The judge said the local clinic’s “robust testing” will pick up on any changes going forward in terms of a resurgence of the virus.

“Are we going to have more cases? Yes. It’s not gone. But if we see it ticking up, we might delay going to 50 percent,” Howard said, referring to the governor’s goal of reopening businesses to 50 percent capacity in Phase Two on May 18.

Howard also urges everyone to continue to follow social distancing guidelines and says older folks should continue to limit going out.

“There is no ‘stay at home’ order, but that does not mean we should not assume responsibility for our own protection and to protect others,” he said.

Adopting a uniform approach to fighting the virus is also important, the judge said.

“Gov. Abbott is the quarterback. He’s called the play, and we’ll do better as a team running the same play,” Howard said.

/https://thumbnails.texastribune.org/sM7am4wZHk4PLCKHp8rcDBFQk-U=/filters:quality(70)/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/1effceeacd0a4e3f315159cd66a917d8/County%20Judge%20John%20Howard%20framed.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/6838b4f03f1200a6255c1607de0fbf1e/Clarendon%20Jim%20Fox%20TT%2004.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/45bdbe75a2e4082a8c1d454edcb41883/Clarendon%20TT%2001.jpg)

Reader Comments